In the “capital of peace,” the palatial grounds of the United Nations Office at Geneva were meant to embody the 20th-century ideal of a postwar world — when countries might seek to avert conflict through diplomacy. During the thousands of meetings held at the Palais des Nations each year, delegates press openly and passionately for their convictions. And yet for 15 human rights activists in March 2024, the U.N. complex held risks.

Fearing retribution from the Chinese government against their families in mainland China and Hong Kong, several of the activists were no longer willing to set foot inside the diplomatic site. Instead, they gathered for a secret meeting on the top floor of a nondescript office building nearby. They were there to discuss human rights abuses in China and Hong Kong with the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, Volker Türk.

“We took all of the necessary precautions,” Zumretay Arkin, vice president of the World Uyghur Congress, which advocates for the rights of the Turkic ethnic group native to China’s northwest Xinjiang region, told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Arkin and her colleagues were meeting in the offices of the International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), an independent organization that trains activists in U.N. advocacy. But minutes before Türk and his aides were due to arrive, two women and two men appeared outside the office. “How can I help you?” asked an ISHR staffer as he opened the door, according to an account he gave to ICIJ.

One of the women announced that she and the group, who claimed to be from the “Guangdong Human Rights Association,” had arrived for a meeting, though they weren’t invited. She pressed for information as her associates peered through the glass, but the staffer denied a meeting was taking place. “I just disengaged from the conversation, and they left,” the staffer told ICIJ. (ISHR says it submitted a statement to U.N. authorities a week later, and also reported the incident to Swiss authorities.)

Then two Uyghur activists left the office for a smoke. They later reported that a figure in the back of a black Mercedes-Benz van with tinted windows appeared to photograph them. People matching the description of the Guangdong group entered the same vehicle before it pulled away.

“This was an act clearly aimed at intimidating and clearly aimed at sending a message to everyone that was here,” said Raphaël Viana David, a program manager at ISHR. Arkin told ICIJ she believes the Guangdong group was sending a signal from the Chinese government: “We’re watching you. We’re monitoring you. You can’t escape us.”

The incident is one of dozens of similar examples ICIJ and its media partners have heard from representatives of the Chinese diaspora — pro-democracy activists, members of ethnic and religious minority groups and others — whom the Chinese government has tried to threaten into silence around the world. The findings are part of China Targets, an investigation by ICIJ and 42 media partners that explores how the long arm of the Chinese state targets critics of the government beyond its own borders — including at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, the heart of the U.N. human rights system.

ICIJ and its partners spoke to 15 activists and lawyers focused on human rights in China who described being surveilled or harassed by people suspected to be proxies for the Chinese government, including those from Chinese nongovernmental organizations. These incidents occurred both inside the Palais des Nations and in Geneva at large. Some activists say their family members, who they believed were pressured by Chinese authorities, asked them to stop speaking out or warned them of the dangers of their activism. U.N. authorities have also reported activists and lawyers being threatened with physical assault, rape and death.

The Palais des Nations, near the shore of Lake Geneva, is where the U.N. Human Rights Council, a body of 47 member states, meets under a domed ceiling no less than three times a year. Geneva is also home to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, which investigates, monitors and condemns atrocities worldwide.

Members of nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, can observe sessions and take to the floor of the Human Rights Council to make statements. It’s a space where survivors and family members of victims can meet face-to-face with the representatives of perpetrators. NGOs provide essential facts and on-the-ground testimony to U.N. experts, officials and diplomats.

Over the past seven years, however, a growing army of Chinese NGOs has descended on the Palais des Nations. Their delegates seek to disrupt and drown out criticism of China, heaping praise on their government.

“It’s corrosive. It’s dishonest. It’s subversive,” said Michèle Taylor, who served as U.S. ambassador to the Human Rights Council from 2022 until earlier this year. Taylor said that China-backed groups “are masquerading as NGOs” as part of a broader effort by Beijing “to obfuscate their own human rights violations and reshape the narrative around China’s actions and culpabilities.”

And their presence is being felt.

“The impact of our work is not the same as if we could do all this openly and in person without fear of reprisals,” said Renee Xia, who runs Chinese Human Rights Defenders, a U.S.-based coalition of advocates. “We don’t know who is recording or videotaping or writing down.”

Thousands of NGOs at the U.N. hold consultative status, granting them certain privileges with the expectation that they act free from government interference. But an ICIJ analysis of 106 of these NGOs from mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan reveals that 59 are closely connected to the Chinese government or the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Forty-six are led by people with roles in the government or the party. Ten accept more than 50% of their funding from the Chinese state.

It’s corrosive. It’s dishonest. It’s subversive.

— former U.S. ambassador to the Human Rights Council Michèle Taylor

In Geneva, government-organized nongovernmental organizations, like the dozens identified by ICIJ, are dubbed “GONGOs.” “It’s paradoxical,” said Titus Chen, an international relations professor at Taiwan’s National Chengchi University. “An NGO is not supposed to be organized by the government.”

Today, China is one of the most powerful member states at the U.N. It’s one of the five permanent members of the Security Council, alongside the United States and Russia. China is also expected to fund one-fifth of the U.N.’s regular budget this year — more than any other country except the U.S. With the return of Donald Trump to the White House and the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Human Rights Council, a vacuum has opened — one China is poised to fill.

The Chinese government stands alone in the seriousness of the threat it poses to the global human rights system, according to Kenneth Roth, who ran Human Rights Watch for nearly 30 years. “To deter condemnation of its severe repression, foremost its mass detention of Uyghurs, Beijing has proposed to rewrite international human rights law,” he told ICIJ.

China has used its clout to garner praise from other U.N. member states. It has also restricted independent experts’ access to the country and stopped internal critics from leaving. And when exiled critics come to Geneva, China’s representatives try to block and intimidate them.

“The U.N. is one of the only forums where we can raise our cause,” said Arkin, who at 10 moved with her family to Montreal from Urumqi, the capital of China’s Xinjiang region, to escape anti-Uyghur discrimination. But, she said, “it’s become one of the places where these governments carry out their repression.”

With autocracy on the rise globally, independent organizations at the U.N. carry a heavier burden to speak out about atrocities and persuade those who can to take action. If China’s power continues to go unchecked by U.N. authorities, it threatens the credibility of the institution in its efforts to monitor and document violations and abuses not just in China, but all over the world.

A ‘deadly reprisal’

More than a decade before the activists’ meeting at the International Service for Human Rights, Cao Shunli, a prominent Chinese human rights activist, was abducted while traveling to the same offices.

Cao had pressed the government to let citizens contribute to a report Beijing was submitting to the Human Rights Council ahead of its 2013 review on China. That summer she staged a two-month-long sit-in outside the Foreign Affairs Ministry in Beijing. She had already been detained several times for her activism.

In September, Cao, 52, tried to board a flight from Beijing Capital International Airport to Geneva, where she planned to attend a training program on U.N. human rights advocacy. Instead, she disappeared. (Several other activists and lawyers from other Chinese cities were reportedly interrogated and warned not to attend the same training program, U.N. authorities said.)

It would be weeks before Chinese authorities confirmed to Cao’s family that she was being held at Chaoyang District Detention Center in Beijing, and had been charged with “picking quarrels and making trouble.” According to reports, Cao, whose health rapidly deteriorated, was denied adequate medical care. She died of multiple organ failure in March 2014 after being moved to a military hospital some days earlier.

During a 2015 session of the Human Rights Council, China said that Cao was “by no means a human rights defender.” It has also said that “no one suffers reprisal for taking part in lawful activities.”

But an internal government document leaked from the public security bureau of Tekes County, Xinjiang, issued eight months before Cao was blocked from leaving China, reveals tactics used to control any perceived threats to national security, including regime critics. The PowerPoint presentation for domestic security officers provides instructions on border control, including preventing citizens from taking part in events “such as an invitation for human rights training from human rights organizations abroad.” The document was shared with ICIJ by Adrian Zenz, director of China studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

Cao’s death stood out as a powerful warning shot. The “deadly reprisal” — as human rights groups referred to it — has discouraged other activists from traveling abroad to engage with the U.N. in Geneva. A decade later, the participation of Chinese human rights defenders in U.N. activity has dropped to a record low, according to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Meanwhile, ICIJ found, the number of Chinese NGOs with U.N. consultative status has almost doubled since 2018. That year, mounting evidence of detention camps in Xinjiang gained international attention, followed by Hong Kong security forces’ brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in 2019. ICIJ’s analysis of the 106 Chinese NGOs shows that 59 aren’t independent of the government or the Communist Party. Instead, they’re GONGOs. In at least 46 of these organizations, directors, secretaries, vice presidents or other high-level staff also hold positions in government departments or with the CCP. In one extreme example, the current secretary-general of a ubiquitous NGO is also the human rights director at the CCP Central Committee Publicity Department, also known as the propaganda department. (A former secretary-general held both positions as well.)

Liu Pengyu, a spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not directly respond to questions about Beijing’s deployment of NGOs at the U.N. in Geneva. Instead, Liu wrote in an email to ICIJ that China had contributed “constructively to global human rights governance.”

“At the international level, China has put forward a series of proposals at the UN Human Rights Council on promoting human rights through cooperation and development, and on advancing economic, social, cultural rights as well as the rights of specific groups,” he said.

The U.N. Human Rights Office told ICIJ in a statement that it works to secure space for independent organizations but that it cannot start differentiating between “authentic” and “non-authentic” NGOs and that such a distinction was unworkable and potentially open to abuse.

The passage of Hong Kong’s national security law in 2020, which criminalized “colluding with foreign forces,” and further legislation in March 2024 has heightened the risks for activists there as well. One Hong Konger, now living overseas, told ICIJ that those who attend the U.N. are mostly in exile. “The situation is that many of us don’t want to go inside the Palais, but there are still some who will. … We have to be careful.”

As these voices fade out, the ones doing China’s bidding are increasingly dominant.

The CCP’s smokescreen

The International Service for Human Rights told ICIJ it has identified the two women from the group that tried to attend the March 2024 meeting at its offices; ISHR said it recognized the women from details it saw online about their activities in Geneva at the time. The woman who spoke to the ISHR staffer is Zhou Lulu, a Chinese Communist Party branch secretary and vice dean of Guangzhou University’s Institute for Human Rights, according to ISHR. Guangzhou is the capital of Guangdong, the Chinese province the group claimed to be from. ISHR said she was accompanied by Wang Shuqi, who, according to China’s Global Times, is an assistant researcher at the Human Rights Research Center at the Northwest University of Political Science and Law in Shaanxi province.

Asked in a telephone call whether she tried to attend ISHR’s offices as a representative of the Guangdong Human Rights Association, Zhou said she couldn’t recall: “I did so much since that journey,” she said. “So I don’t remember which one. I can’t remember so clearly.”

At the time of the meeting, Zhou was in Geneva with a delegation that included experts and lawyers specializing in “religious freedom, history, human rights and counterterrorism,” according to a Chinese state-run broadcaster. They were seeking “to showcase China’s achievements and best practices.”

Raphaël Viana David, the ISHR program manager, said he encountered Zhou in the Palais des Nations one day after the meeting taking photos of panelists at an event where a Tibetan exile was among the speakers. Viana David said he asked Zhou to delete the photos and that, after some resistance, she eventually complied. Photography by NGO representatives is prohibited at side events inside the Palais des Nations without prior authorization.

Zhou had given a speech at the Human Rights Council just days earlier as a representative of the Chinese Society for Human Rights Studies, or CSHRS. The Beijing-based group describes itself as “China’s largest non-governmental organization devoted to promoting human rights.” According to ICIJ’s analysis, the NGO qualifies as a GONGO because three of its top leaders hold positions with the CCP, and it made pro-China statements at the Human Rights Council.

Wang, who did not respond to questions from ICIJ, was also in Geneva in mid-March 2024, speaking at a U.N. side event. According to ISHR, she has previously spoken at the Human Rights Council as a delegate of CSHRS. The organization got a high-profile nod in a 2022 speech by Chinese President Xi Jinping when he spoke on human rights to some of the highest ranking figures within the Communist Party. Xi urged China to “play an active role in the human rights affairs of the U.N.” and added that “full play” should be given to CSHRS in order to build China’s influence.

Titus Chen, who in 2019 published an exhaustive analysis of speeches, declarations and announcements from the CSHRS website, calls the group a mouthpiece for Communist Party propaganda. “They are two sides of the same coin,” Chen said.

CSHRS did not respond to detailed questions from ICIJ; however, a representative of the organization said over the phone: “We are simply an academic institution.”

All Chinese NGOs must register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs and be monitored by a government department or the CCP; this alone doesn’t qualify them as GONGOs. But ICIJ’s analysis shows the extent to which the government or the party interferes with the independence of some Chinese NGOs with U.N. consultative status. For example, 53 of these organizations publicly pledge loyalty to the Communist Party on their websites or in official documents. And 12 go even further, allowing the party to intervene in their decision making, which can include approving large donations or leadership appointments.

“GONGO” is a term for government-organized nongovernmental organizations — groups that are expected to be independent but, instead, hold close ties to governments or political parties. Connections can be through funding or staffing, or reflected in public statements.

At the United Nations in Geneva, these puppet organizations push state agendas and stifle independent voices by monopolizing speaking opportunities and using intimidation tactics, such as surveillance.

ICIJ analyzed 106 NGOs with U.N. consultative status from mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan listed under China in a U.N. database as of March 2025. (This reflects the U.N.’s own classification. Taiwan is self-governed by an elected government.) In collaboration with media partners on several continents, ICIJ reviewed the NGOs’ financial reports, charters, and websites in English and Chinese to assess how connected they are to the Chinese government and Communist Party.

Not all Chinese NGOs qualify as GONGOs. However, ICIJ has identified 59 GONGOs at the U.N. by reviewing three criteria:

- A current government or party official holds an organizational leadership role, such as secretary, vice secretary or director.

- More than half the annual budget comes from the government.

- Pro-China statements have been made in-person or online during Human Rights Council sessions.

ICIJ classified NGOs that matched at least one criterion as GONGOs; 28 matched two or more.

The U.N.’s Economic and Social Council awarded CSHRS consultative status back in 1998. NGOs with consultative status can present written and oral statements to the Human Rights Council, lobby in the corridors of power and host side events in the Palais des Nations. Reporters from ICIJ and its media partners attended several of these events and witnessed Chinese diplomats lambasting speakers — and NGO representatives doing the same.

For example, at a September 2024 panel event, speakers had just finished discussing the plight of Uyghurs detained in camps in Xinjiang when a woman from the audience asked a question: “Have you ever been to China?” She was from the U.N. Association of China, an NGO with U.N. consultative status — another GONGO, according to ICIJ’s analysis. She then accused the panelists of being “full of lies and rumors,” urging them to pay more attention to racism and gun violence in the U.S.

Of all the Chinese NGOs that spoke at the Human Rights Council sessions from 2018 to 2024, ICIJ found that CSHRS was the most active, appearing more than 300 times on speakers lists (both in person and online). The majority of its statements can be classified as pro-China, according to an ICIJ analysis of data collected by ISHR. Dozens of other Chinese NGOs also flooded the sessions with praise of the Chinese government — the vast majority of those were GONGOs.

After the March incident in Geneva, ISHR says it submitted photographic evidence to support its account of what happened — including the identities of the CSHRS associates — to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Each year, the U.N. secretary-general publishes a report detailing alleged reprisals and acts of intimidation for cooperation with the U.N. in the field of human rights. The aim of the report, the office explained to ICIJ in a statement, is to promote accountability by calling out the perpetrators. But the Guangdong group episode went unmentioned in the secretary-general’s report in 2024. The office told ICIJ “the information it received raised concerns but did not fully meet the standard criteria (threshold) for inclusion in the report.”

The office also said it reviewed ISHR’s statement and evidence and “then brought the situation to the attention of the Chinese Government, in accordance with our usual practice.” It added that it had had no contact with the China Society for Human Rights Studies regarding the incident.

Creating an army of GONGOs

Chinese diplomats routinely implore U.N. authorities to bar China’s critics. Letters provided to ICIJ by Emma Reilly, a former U.N. human rights officer, show persistent lobbying of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to refuse Tibetans and Uyghurs accreditation to the Human Rights Council, labeling them “secessionists.” As early as 2001, the Chinese ambassador requested the then high commissioner to “avoid meeting with any member of organizations against the Chinese government, such as Falun Gong, Tibetan and the so-called exiled dissidents, just as you did in the last few years.”

Since Xi’s reelection as Communist Party general secretary in 2017 and president the following year, China has sought greater influence within the U.N. human rights system and become more aggressive in silencing dissent.

In 2017, the Chinese government first donated to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, giving $100,000; that figure rose to $4 million by 2023. These pledges are overshadowed by those of several other member states. (The U.S. gave more than $36 million in 2024.) But unlike most of the leading donors, the Chinese government carefully earmarks all the money for specific causes, according to the office’s annual report. Some of China’s donations have gone to funding special rapporteurs for the right to development, rights of migrants as well as unilateral coercive measures — often referred to as sanctions ($1.2 million in total between 2019 and 2023). The special rapporteur on these measures visited China in May 2024 and then called upon states to lift sanctions imposed on the country, citing their disproportionate impact on parts of Xinjiang’s economy.

The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination sounded the alarm over the detention of ethnic Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in August 2018. With no official figures, the committee warned that the number of detainees could be more than a million. The next month, former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet, in a speech as U.N. high commissioner for human rights, called the allegations “deeply disturbing” and requested Beijing allow her office to visit.

But by that point, a Chinese government-led campaign was already fueling the expanding presence of Chinese NGOs in Geneva. In 2020, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that in recent years it had “vigorously supported and guided domestic NGOs to ‘go global’ ” at the U.N. Since 2021, provincial and municipal governments have also arranged seminars and step-by-step online tutorials on how to apply for U.N. consultative status.

“The Chinese government is clearly using NGOs as a tool,” said Rana Siu Inboden, senior fellow at the Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the University of Texas at Austin. “They are encouraging them, helping them, guiding them, coaching them through how to get this [consultative] status. … And then once they’re [at the U.N.], you can see how their statements, whether it’s in the Human Rights Council or elsewhere, serve the government.”

In 2024, 33 Chinese NGOs showed up about 300 times on the lists of speakers at Human Rights Council sessions. There were only three of them in 2018. None criticized China, ICIJ’s review of their statements found. Out of hundreds of statements those NGOs made in person and online from 2018 to 2024, a clear majority were pro-China, according to data collected by ISHR and analyzed by ICIJ.

When Bachelet finally visited China for six days in May 2022, she ignited a firestorm. International human rights groups publicly chastised her for failing to forcefully condemn China’s record. Within weeks she announced she would not seek another term for “personal reasons.”

Meanwhile, Beijing was ratcheting up its campaign to keep her findings buried — even as her own staff reportedly pushed her to publish them. A group of nearly 1,000 organizations, including 20 Chinese NGOs with U.N. consultative status, wrote an open letter in the state-run newspaper China Daily imploring Bachelet “not to release an assessment full of lies.”

At 12 minutes to midnight on the final day of Bachelet’s term, her office published the report. It documented rape and torture inside detention centers as well as forced birth control and extensive surveillance in Xinjiang. Bachelet concluded that China’s actions could amount to “crimes against humanity.”

“It was an extraordinary moment to see the U.N.’s flagship human rights investigative body level that allegation at one of the most powerful governments in the world,” said Sophie Richardson, who was then China director at Human Rights Watch. But when the Human Rights Council’s member states voted on a proposal to hold a discussion about the situation in Xinjiang, President Xi called several heads of state, pressing for their support. The measure was defeated by two votes, and China’s allies broke into applause.

Eleven countries abstained from voting, avoiding China’s wrath. And several Muslim-majority countries sided with Beijing, including Indonesia, Pakistan and Qatar. On Twitter the spokesperson for Beijing’s Foreign Ministry declared it a “victory for developing countries,” adding that “human rights must not be used as a pretext to make up lies and interfere in other countries’ internal affairs, or to contain, coerce & humiliate others.”

With Bachelet gone, the fallout landed on the desk of her successor: Volker Türk. The Austrian human rights lawyer, U.N. careerist and long-term confidant of the secretary-general said nearly three months into the job that he felt duty-bound to follow up on the report’s findings.

In August 2024, nearly two years after Bachelet’s report, a spokesperson for Türk, who has led the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights since October 2022, said in a statement that “many problematic laws and policies remain in place” and that “allegations of human rights violations, including torture, need to be fully investigated.” But the statement stopped short of characterizing such violations as possible crimes against humanity.

Since the Trump administration took office in January 2025, its sweeping foreign aid cuts have further plunged many China-focused human rights groups into a vulnerable position.

Kenneth Roth, formerly of Human Rights Watch, told ICIJ that while Türk has been outspoken on some issues, such as conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine, by pursuing quiet diplomacy with China instead of outright condemnation “he’s playing into Beijing’s game plan.”

A spokesperson for Türk told ICIJ in a statement that he was committed to engaging in “frank discussions” with the Chinese government and publicly advocating for victims. The spokesperson said the office is “always guided by the goal of helping improve human rights protections for the people on the ground.”

Among the world’s autocracies

As the U.N. has struggled to stand up to China, its diplomats and their allies have become gatekeepers for NGOs seeking U.N. consultative status. An organization that isn’t set up by a government or international agreement can be deemed an NGO, according to the rules set out in a 1996 U.N. resolution. The criteria for earning consultative status include transparent and democratic decision making.

Copies of NGOs’ charters, certificates of registration and most recent financial statements must be submitted as part of the application process. NGOs also complete a questionnaire in which they must disclose their links to governments, including whether any government officials are on their boards or executive teams. They need to state whether they receive government funding and how much. Applications are reviewed by a team of U.N. officials who perform some basic vetting before they are scrutinized by diplomats at the U.N.’s Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations in New York.

It’s an unusual mix of member states mingling, said one diplomat who sits on the committee and spoke on the condition of anonymity. Over the past 10 years, half of its member states qualify as “authoritarian regimes,” according to an ICIJ review using criteria from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2024 Democracy Index. Cuba, Nicaragua and Pakistan have sat on the committee alongside China since at least 2015 — all authoritarian regimes according to EIU’s index.

A delay tactic to block NGOs seeking consultative status is commonplace. Diplomats on the Committee, for example, can ask a trivial question, automatically deferring an NGO’s application. China has consistently outpaced other committee members in its obstruction, according to a new analysis by ISHR — and sometimes they work together. China coordinates closely with its allies, each taking turns to block NGOs on behalf of other members, according to a U.S. diplomat familiar with the process.

NGOs that campaign against human rights violations in China and Hong Kong no longer stand a chance to achieve U.N. status, said Carmen Lau, of the Hong Kong Democracy Council. “Organizations like ours would never be able to apply for the [consultative] status in the U.N.,” she added. “We always partner with [other] NGOs … to advocate in the U.N.”

There have been repeated calls for politicized deferrals to cease — including from the high commissioner’s office in Geneva. But the practice continues, and the proportion of independent human rights NGOs participating in U.N. sessions is in danger of receding compared with groups that back the Chinese government.

‘China’s playground’

Before the sun had fully risen in Geneva on a January morning in 2024, a long line of Chinese NGO delegates had formed at the security office by the entrance to the Palais des Nations. They had arrived to secure a place to listen in on the Human Rights Council’s first review of China in about five years.

At the session, Chinese Ambassador Chen Xu boasted that his government had lifted nearly 100 million people out of poverty and “eradicated absolute poverty once and for all.” Another 161 countries spoke, each allocated 45 seconds. The division of allegiances was stark and predictable. The U.S. condemned China for “the ongoing genocide” in Xinjiang. Russia, Iran and Venezuela lauded the Chinese government’s achievements.

Mao Junxiang, executive director of the Human Rights Research Center at China’s Central South University, wrote an essay after attending the review with the China Society for Human Rights Studies, in which he observed that a struggle with “foreign anti-China” NGOs over seating underscored the “politicization” of the day. He also accused them of submitting “false and defamatory materials” against China to the U.N.

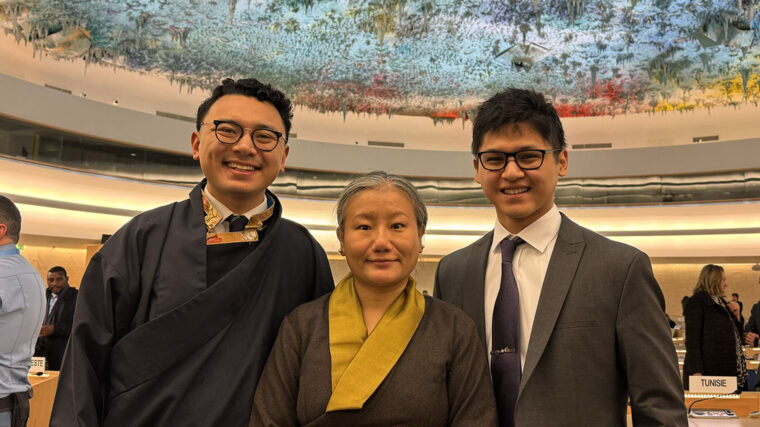

Topjor Tsultrim, a 25-year-old activist in New York of Tibetan heritage, said there was an “air of animosity” as he waited in line with other NGOs to enter the Palais des Nations. Once inside, as he approached the room where the review would take place, Tsultrim said at least one individual with NGO accreditation appeared to use a smartphone to photograph or record him and others, according to a report later filed with the U.N. In the report, Tsultrim, now communications director for Students for a Free Tibet, said security staff were initially dismissive, though one officer eventually spoke to the person with the phone.

Rushan Abbas, co-founder of the U.S.-based Campaign for Uyghurs whose sister was arrested in Xinjiang nearly seven years ago and remains in prison, made a similar claim. Nine days after the review in Geneva, Abbas submitted testimony to the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China, writing, “Another pro-China attendee was taking pictures of Tibetan and Uyghur rights defenders as we were standing in the line to enter the hall, and unfortunately, it took repeated cries from activists to get the U.N. security to stop this individual.”

Matthew Brown, a public information officer for the Human Rights Council, told ICIJ that U.N. staff alerted to such incidents “intervene directly and follow up with Security personnel if necessary,” adding that “many times, photographs have been deleted from phones.”

Abbas told ICIJ that “even after we got in, we were sitting there, those Chinese GONGOs were taking pictures of us.”

“I got photographed when I was on the floor [of the chamber],” said Sophie Richardson, the former China Director at Human Rights Watch, who sat between two GONGO representatives. “The guy took a picture of the screen of my laptop [as she live-tweeted the session]. I said to him, ‘You know this is public, anyway?’ Then he just took a picture of my face.”

For her part, Abbas told ICIJ, “I did not report [this] to the U.N. authorities because I lost faith in them, as China was acting … like the U.N. was its playground.”

At a session months later where NGOs were allowed to speak, the Chinese ambassador accepted and rejected recommendations presented in a report. There were just 10 speaking slots for nongovernmental organizations. Half of these were occupied by Chinese NGOs, all of which ICIJ identified as GONGOs.

“They played the support role,” said Titus Chen, the professor of international relations in Taiwan. “I believe they were each given different role for the same agenda to tell the [Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review] … people in that session that China is doing a good job in protecting human rights in every single way.”

The succession of people representing Chinese NGOs promoted the country’s economic development, science and innovation, and environmental protections. A woman speaking for the Beijing Crafts Council and the China Ethnic Minority Association may seem like an unlikely voice at the U.N., but her presence made clear just how far China has gone in changing the tenor of discussions about it.

After praising China’s longtime support of ethnic arts, “including handicrafts,” she went on to tout the government’s respect for ethnic traditions in places such as Xinjiang. The speaker proclaimed that “China is open for foreign organizations and individuals who sincerely love ethnic culture and arts,” but, lest anyone conclude that the speech was all feel-good gratitude, she closed by adding, “rather than ignore the truth and smear our efforts so as to undermine our stability and development. … Thank you.”

Contributors: Sylvain Besson (Tamedia); Maria Christoph, Frederik Obermaier (paper trail media/ZDF/DER SPIEGEL); Justin Wong (The Post/Stuff); Greg Miller (The Washington Post); Sebastian Kjeldtoft (Politiken); Tobias Andersson Åkerblom (Göteborgs-Posten); Jane Tang (Radio Free Asia); Echo Hui (Australian Broadcasting Corporation); Stefan Melichar (profil); Linda Kakuli (SVT); Simon Leplâtre (Le Monde); Denise Ajiri, Scilla Alecci, Agustin Armendariz, Sam Ellefson, Jesús Escudero, Miguel Fiandor Gutiérrez, Karrie Kehoe, Delphine Reuter, Joanna Robin, David Rowell (ICIJ)